Why You Can’t Visualise the Final Image Yet — And How Photographers Actually Learn It

When I first got into landscape photography, I spent countless hours watching YouTube tutorials and reading blog posts. Much of it was helpful, but one piece of advice kept coming up that never felt right:

“You need to visualise the final image before you press the shutter.”

I understood the idea — I use visualisation all the time in skiing — but in photography it didn’t come naturally. For some standard shots, sure. But for most scenes, I simply couldn’t picture the end result.

But the truth was, visualising the final image didn’t come easily, even though I understood the idea.

Over time, with more experience, I noticed I was starting to visualise naturally. It genuinely helped me make better photos. So what changed?

The answer was simple: Experience.

1. Why Beginners Struggle With Visualisation

In the beginning, it wasn’t just that I lacked the technical ability to create certain images — I didn’t realise those techniques were options for the scene I was looking at.

I knew other photographers made dramatic long exposures, soft water, minimal fog scenes, high-contrast black and whites… I’d seen those photos before.

But I didn’t yet understand:

- when a scene in front of me had the potential to become one of those images

- what settings I would need to make it happen

- how light or conditions would react to different choices

- what editing could do to shape the final mood

So even though I knew these types of images existed, I had no idea how to apply those possibilities to what was right in front of my lens.

And if you don’t know how to get a certain result — or don’t even recognise a scene as having that potential — how can you visualise it?

2. Why Instant Feedback Helps — But Only Gets You Part of the Way

One of the great things about modern digital cameras is instant playback. You can take a shot, look at the back of the camera, and immediately see what worked and what didn’t. Auto modes can actually help beginners start to visualise by letting them:

- see how a scene looks when the camera makes the decisions

- quickly adjust compositions

- experiment with angles and framing

- get immediate feedback on exposure

This alone teaches you a lot, and it’s a great early stepping stone.

But instant playback only shows you a small part of what’s possible.

To fully unlock visualisation, you eventually need to go beyond letting the camera choose everything. That’s when you start learning how different modes change the feel and mood of a photograph:

- Shutter Priority (S / Tv) teaches you how motion changes with different shutter speeds — whether water appears silky, frozen, or chaotic, and how wildlife behaves in the frame.

- Aperture Priority (A / Av) shows you how depth of field affects isolation, storytelling, and the emotional weight of a subject.

- Focal length changes compression, scale, perspective, and how the landscape fits together — something you only learn by switching lenses and comparing results.

- Manual Mode (M) ties everything together, giving you full control so you can intentionally shape a scene instead of accepting whatever auto mode gives you.

Once you understand how each of these choices affects the final image, you start recognising scenes that could become something interesting. You begin predicting how the camera will interpret them — and how you want to interpret them.

So yes — auto mode and instant playback are fantastic tools for learning. They give quick feedback and help you start seeing possibilities.

But to truly visualise the final image in your mind before taking the shot, you need the experience of shooting in different modes, trying different settings, and seeing firsthand how those decisions change both the technical and emotional result.

That’s when your visualisation begins to expand — not just reacting to what the camera shows you, but predicting what you can create.

3. Learning to See: The Artistic Side of Visualisation

Visualisation isn’t just about knowing your camera settings — it’s also about learning to see the world in a photographic way. When you’re new to photography, most of the subtle things happening in a scene simply don’t register yet. Your eyes take everything in at once, and it’s hard to isolate what actually makes a photograph work.

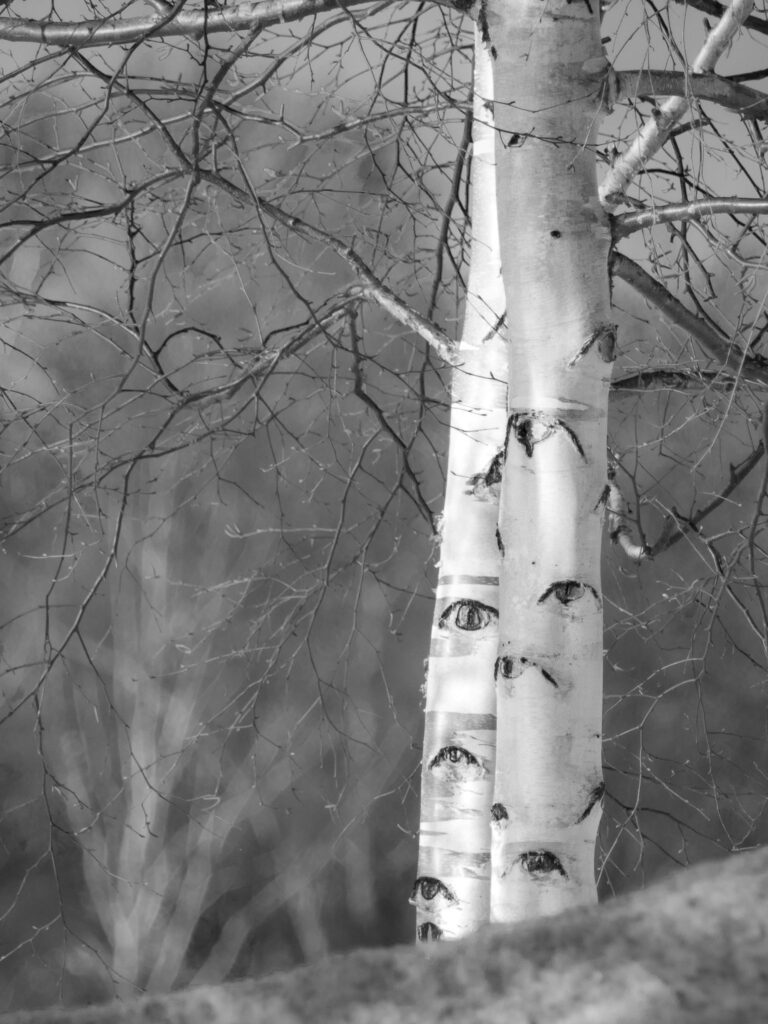

Over time, through shooting and reviewing your results, you start to notice how light behaves. You begin to see how it shapes a subject, how shadows reveal texture, and how the direction or quality of light can completely change the mood of a scene. Fog, which at first just looks like atmosphere, slowly becomes something you recognise as a tool — a way to simplify a busy landscape and create calm, minimal compositions. Snow, which beginners often treat as just “white stuff,” becomes something you understand as a natural softener of contrast and a way to bring gentle tones into an image.

You also start noticing emotional elements. Isolation suddenly becomes a compositional choice, not an accident. A single tree in an open field, or a lone rock in a river, becomes a way to express quiet or simplicity. Even perspective — where you choose to stand, how high or low you place the camera — begins to influence the mood you’re trying to communicate.

If you’re curious how this process shaped my own work, I wrote a post about how I discovered my photography style through years of trial, error, and simplifying the scenes I was drawn to.

None of this jumps out at you when you first start photographing. These are patterns you only see after you’ve shot a lot, looked at what worked, and reflected on why certain images feel stronger than others.

This idea ties directly into something Ansel Adams wrote:

“The first step towards visualization… is to become aware of the world around us in terms of the photographic image. We must teach our eyes to become more perceptive.”

As you slowly train your eye to become more perceptive, you begin to anticipate the photograph before you even raise the camera. That growing awareness is one of the foundations of visualisation.

4. What Ansel Adams Said About Visualisation — and How We Can Learn to Apply It Today

Ansel Adams — often called the father of landscape photography — considered visualization one of the most important concepts in the entire craft. His descriptions of it were thoughtful and deeply artistic.

He wrote:

“Visualization is a conscious process of projecting the final photographic image in the mind before taking the first steps in actually photographing the subject.” — Ansel Adams, The Negative

And also:

“To visualize an image is to see it clearly in the mind prior to exposure, a continuous projection from composing the image through the final print.”

For Adams, visualization wasn’t just seeing a picture in your head — it was an entire emotional-mental process that guided how he interpreted the world.

He believed:

“The first step towards visualization… is to become aware of the world around us in terms of the photographic image. We must teach our eyes to become more perceptive.”

This idea still holds enormous value today.

But here’s the key point that’s often missed:

Adams could only visualize so clearly because he had years of technical knowledge and darkroom experience behind him.

He didn’t visualise in a vacuum. He visualised based on:

- knowing how film responded to different tones

- understanding how contrast would print

- mastering the Zone System

- anticipating how dodging and burning could shape a scene

- decades of printing experience

- thousands of experiments and failures

His visualization was the result of experience, not the starting place.

And he acknowledged that other photographers reach this ability in different ways:

“The best photographers… ‘see’ their final photograph before it is completed, whether by conscious visualization or through some comparable intuitive experience.”

Notice that word: experience. That’s the bridge.

Adams wasn’t saying beginners should magically know how to pre-visualise a finished print. He was describing what becomes possible after you’ve trained your eye, learned how your tools behave, and built familiarity with how a scene translates into a finished photograph.

So the real question becomes:

How do we learn to visualize the way Adams described?

Not by forcing it.

Not by expecting it from day one.

But by developing the same foundations he built his vision on:

- experimenting

- learning to see

- understanding light

- practising exposure

- building editing skill

- reviewing results

- and gradually forming an internal “visual library”

Visualisation isn’t something you start with. It’s something you grow into — just like Adams did.

5. The Role of Experimentation (The Part Nobody Teaches)

If you want to learn how to visualise, the path isn’t complicated — but it does require something that many photographers forget to talk about:

You have to experiment.

Taking photos just to see what happens is one of the most important steps in developing a photographic eye. When you’re new, you simply don’t know what your camera can do, how different choices affect a scene, or how far you can push an idea. Experimentation fills in those gaps.

Start by deliberately trying things you’re unsure about. Learn the rules of composition, use them, and then break them to see how the image feels. Change your angles, frame things in unusual ways, and test ideas even if you’re not sure they’ll work. Shoot the same subject with a wide lens, then again with a telephoto. Try a fast shutter, then a slow one. Compare the results.

Editing is a huge part of this too. When you’re learning, it’s actually useful to:

- over-edit

- under-edit

- push sliders too far

- try colour styles that you think won’t work

- rescue a bad photo just to see what’s possible

The goal isn’t to create perfect images — it’s to understand what your tools can do. Even the edits you hate teach you something. Over time, you develop the taste and restraint to edit more intentionally.

Experimentation in the field matters just as much. Try:

- long exposures

- handheld motion blur

- photographing in “bad” light

- shooting scenes that don’t look interesting at first

- using focal lengths you rarely touch

Every one of these attempts teaches you something about how a scene can be interpreted.

As you experiment, you slowly build a mental library of possibilities. You start recognising patterns: this kind of light works well with slow shutter; this kind of fog suits a longer lens; this scene needs contrast; this one needs softness.

This is the real beginning of visualisation — not guessing, but recognising.

And if you stop experimenting, your photography will stagnate. Growth only happens when you keep playing, testing, failing, and trying again.

6. How Editing Teaches You to Visualise

One of the biggest surprises in photography is how much editing shapes your ability to visualise an image before you take it. When you’re new, you simply don’t know what’s possible yet. You might look at a scene and think it looks great, but the photo you take feels flat or boring. That gap between what you saw and what the camera recorded is where editing becomes a teacher.

In the beginning, I tried to rescue weak images by pushing the edits too far. Looking back, many of those early edits were objectively terrible — but they were important. They showed me what looks unnatural, what feels forced, and how quickly an image can fall apart when you lean too hard on a style. They also showed me the opposite: how subtle adjustments in tone, contrast, or colour can completely shift the mood of a photograph.

As you experiment with editing, you gradually build a sense of what an image could become. You learn how far “too far” actually is, how delicate changes influence emotion, and how different treatments suit different scenes. All of that knowledge feeds directly into visualisation in the field.

The more you understand how an image can be shaped afterwards, the easier it becomes to recognise potential before you press the shutter. You start to see the photograph not just as it is, but as it could be.

And that’s the key:

You can’t visualise a photograph until you understand the tools that shape it.

7. Creativity and Reality: You Don’t Have to Be Literal

Another part of learning to visualise is accepting that a photograph doesn’t have to be a perfect record of what was in front of you. Unless you’re doing photojournalism, you’re free to interpret a scene — to emphasise mood, simplify distractions, or guide the viewer’s attention. The camera is only the starting point.

There’s nothing wrong with shaping an image to reflect how it felt, not just how it looked. The important thing is honesty: don’t claim an image is literal if it isn’t. Simply say, “This is what I created.”

As your eye develops, these decisions become more natural and more subtle. You start to recognise, even in the field, the kind of atmosphere or emotion you want to express. And that makes visualisation much easier.

Conclusion: Why Visualisation Comes Later — And That’s Normal

Photographers often tell beginners to “visualise the final image,” but rarely explain how anyone is meant to do that. The truth is that visualisation isn’t something you start with — it’s something you grow into. You develop it by experimenting, making mistakes, editing too much, editing too little, and slowly learning what your camera and your eye can actually create.

The more time you spend outside with your camera, the faster this process happens. Playing, exploring, trying things just to see what they look like — that is the fun part of photography. And without real experience, without curiosity and a bit of chaos, visualisation has nothing to grow from.

So don’t pressure yourself to “see the final image” right away. Go out, enjoy the process, and let your visual imagination develop naturally. It will come.

If you enjoyed this post, feel free to explore more articles on the blog — and if you want updates, behind-the-scenes stories, or tips on photography and creativity, you can join my newsletter as well.